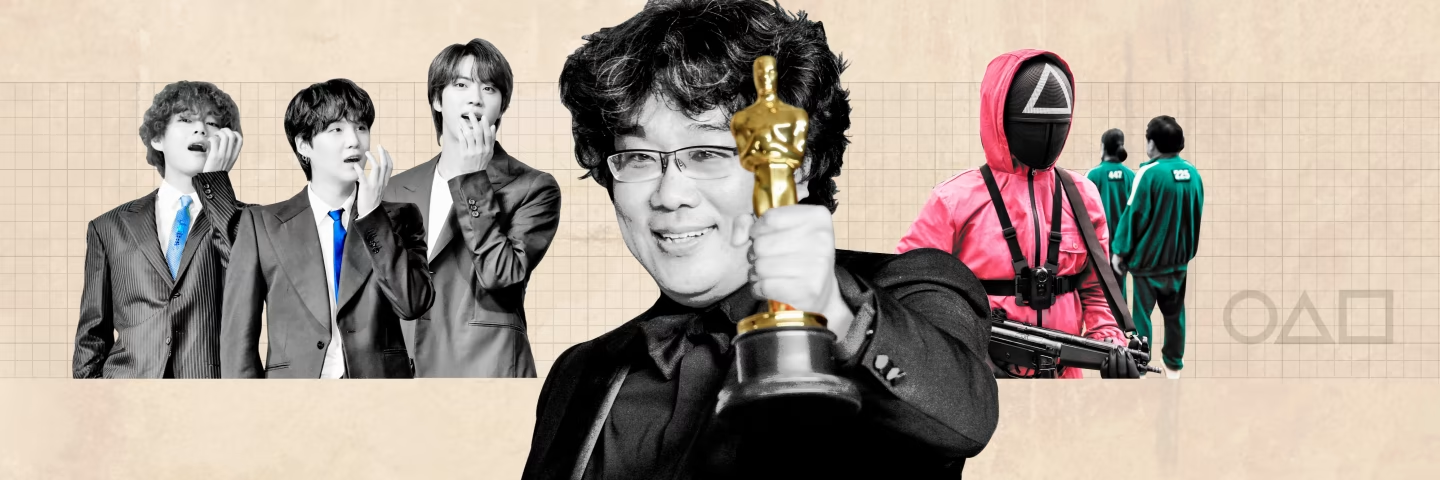

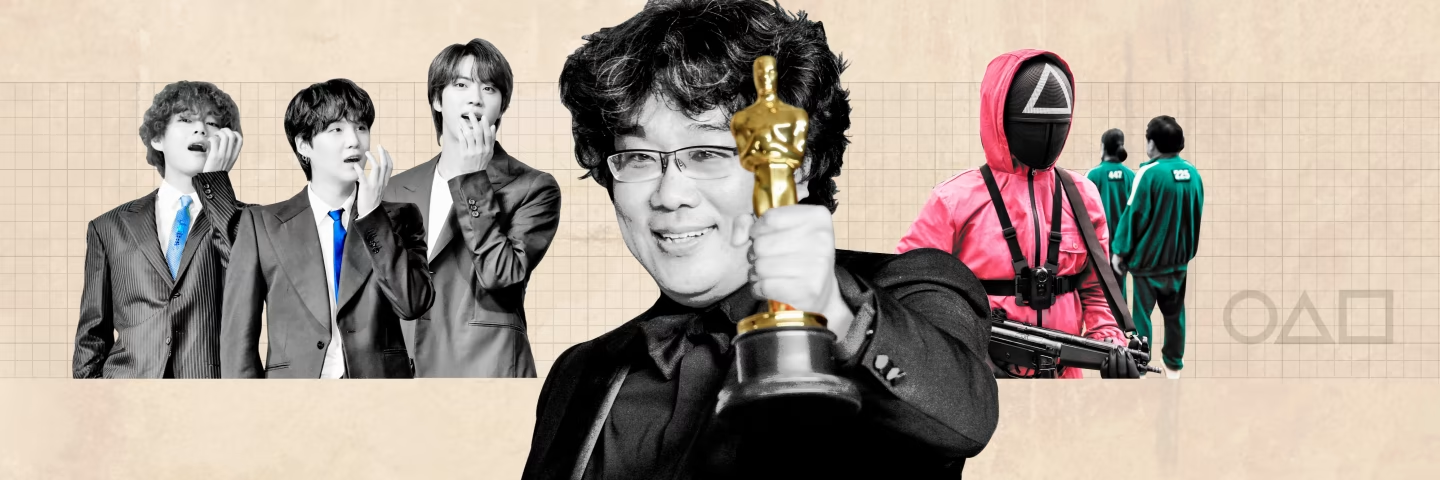

Bong Joon-ho, BTS and Squid Game represent some of South Korea’s biggest entertainment exportsHaving given the world K-pop, Parasite and Squid Game, it now wants to create global platforms to distribute its content

Bong Joon-ho, BTS and Squid Game represent some of South Korea’s biggest entertainment exportsHaving given the world K-pop, Parasite and Squid Game, it now wants to create global platforms to distribute its content

Bernie Cho still remembers his visit to the smoking area of Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris in 2010. The Korean-American music executive, who worked with several high-profile Korean pop acts during his days as a producer and presenter on MTV in the early 2000s, was travelling with a delegation of Korean artists and government officials to stage the inaugural K-pop showcase at an international music festival in Cannes.

Stepping outside in Paris after a long flight from Seoul, he was startled to see dozens of young fans of Epik High, a Korean hip-hop trio he was accompanying to France.

“These were fans I didn’t even know existed, French teenage girls excitedly waving placards,” says Cho. “Then in Cannes, hundreds more turned up — some were even explaining their love for K-pop to me in fluent Korean. That’s when I knew K-pop had the potential to explode.”

In turns saccharine, brutal, and dazzlingly original, Korean content has since bulldozed its way into the global cultural consciousness.

Girl group Blackpink has the most YouTube subscribers of any musical artist in the world, while boy band BTS has a following so organised and devoted that Chinese authorities have come to regard it with the kind of suspicion historically reserved for religious groups like Falun Gong.

More recently, South Korea’s merciless social satires have conquered the heights of film and television respectively. Bong Joon Ho’s Oscar-winning Parasite and Netflix sensation Squid Game — the streaming service’s most-watched show ever — have given global exposure to traditional Korean preoccupations with economic precarity and social violence.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in speaks as Bong Joon-ho, director of the four-Oscar award-winning film ‘Parasite’, reacts during a luncheon at the Presidential Blue House in Seoul, South Korea, in 2020 © Kim Hong-Ju/Pool/ReutersTaken together with South Korea’s huge gaming sector, in 2019 the East Asian country’s entertainment industry was estimated by the state-run Korea Creative Content Agency (KOCCA) to have raked in $107bn in sales revenues. It has left observers searching for answers as to how it managed to break into the global mainstream in ways others — including much larger neighbours China and Japan — have not.

South Korean President Moon Jae-in speaks as Bong Joon-ho, director of the four-Oscar award-winning film ‘Parasite’, reacts during a luncheon at the Presidential Blue House in Seoul, South Korea, in 2020 © Kim Hong-Ju/Pool/ReutersTaken together with South Korea’s huge gaming sector, in 2019 the East Asian country’s entertainment industry was estimated by the state-run Korea Creative Content Agency (KOCCA) to have raked in $107bn in sales revenues. It has left observers searching for answers as to how it managed to break into the global mainstream in ways others — including much larger neighbours China and Japan — have not.

The rise of the Korean entertainment industry bears many of the hallmarks of the country’s success stories in manufacturing sectors like cars and consumer electronics: active state involvement, a willingness to absorb and finesse foreign influences, and a near-pathological export-oriented mindset.

“This is not just a cultural moment,” says Cho. “It’s an ‘overnight success story’ more than 20 years in the making.”

But if the success of Squid Game illustrates the potential for Korean content to captivate global audiences, it has also crystallised a wider dilemma for Korean entertainment companies: how to move from producing content that performs well on foreign platforms such as Netflix or Apple Music to growing its own platforms so that they can emerge as global players in their own right.

“Squid Game showed the world the quality of South Korean content, but creating a global platform is a different story,” says Chan Lee of Petra Capital Management, which has investments in the Korean entertainment industry. “The immediate goal [of these companies] should be to be treated as more than just subcontractors.

Visitors take selfies with a giant doll named ‘Younghee’ from the Netflix series ‘Squid Game’ at a park in Seoul, South Korea © Kim Hong-Ji/Reuters

Visitors take selfies with a giant doll named ‘Younghee’ from the Netflix series ‘Squid Game’ at a park in Seoul, South Korea © Kim Hong-Ji/Reuters A clothing factory owner checks newly made tracksuits inspired by ‘Squid Game’ at his premises in Seoul © Kim Hong-Ji/Reuters“The key thing is to be able to influence the production process,” he adds. “From an investor’s perspective, what counts ultimately is who controls the ecosystem.”

A clothing factory owner checks newly made tracksuits inspired by ‘Squid Game’ at his premises in Seoul © Kim Hong-Ji/Reuters“The key thing is to be able to influence the production process,” he adds. “From an investor’s perspective, what counts ultimately is who controls the ecosystem.”

THE KOREAN WAVE

Aside from renown in the rarefied realm of highbrow cinema, until the 1990s South Korean popular culture went largely unnoticed beyond the country’s borders. That started to change as a wave of creative energy was released in the wake of South Korea’s post-1987 democratic transition.

In the early 1990s, brash western-influenced music acts such as Seo Taiji & Boys challenged government censorship and displaced an old guard of crooners in the affections of young Koreans, fuelling the rise over the course of the decade of a new generation of Korean entertainment companies and talent agencies. They were influenced both by American popular culture and the “idol” pop star assembly line model developed in Japan.

Bernie Cho, president of DFSB Kollective, first realised K-pop’s international potential while at a music festival in Cannes, France © Ore Huiying/Getty/All That Matters

Bernie Cho, president of DFSB Kollective, first realised K-pop’s international potential while at a music festival in Cannes, France © Ore Huiying/Getty/All That Matters Epik High, a hip-hop trio, were one of the first K-pop bands to find teenage audiences outside Korea © Michael Buckner/GettyThe bruising experience of the 1997-98 Asia financial crisis convinced successive South Korean governments to invest heavily in the country’s digital infrastructure and in the promotion of its cultural exports. “The financial crisis convinced policymakers that there was a limit to what could be achieved through the manufacture of physical goods,” says Yong Kwon of the Korea Economic Institute of America.

Epik High, a hip-hop trio, were one of the first K-pop bands to find teenage audiences outside Korea © Michael Buckner/GettyThe bruising experience of the 1997-98 Asia financial crisis convinced successive South Korean governments to invest heavily in the country’s digital infrastructure and in the promotion of its cultural exports. “The financial crisis convinced policymakers that there was a limit to what could be achieved through the manufacture of physical goods,” says Yong Kwon of the Korea Economic Institute of America.

Incentivised by the proliferation of cable TV channels hungry for content, in the late 1990s and early 2000s Korean dramas made inroads across Asia, giving rise to the term hallyu, or Korean Wave.

“Government policy succeeded, but not in the way it might have intended,” says Kwon. “What really mattered was not its efforts to subsidise the creation of content, but the creation of a robust broadband infrastructure that accelerated the disruption of the existing entertainment industry, paving the way for a new generation of producers and consumers.”

Singer Rain performs during a sold-out show at Madison Square Garden in New York in 2006 © Scott Gries/GettyYet, by the mid-2000s the Korean Wave still had not reached beyond Asia. That would require the emergence of technology that would bypass traditional channels and in the words of one industry insider, inject Korean content “straight into the bloodstream”.

Singer Rain performs during a sold-out show at Madison Square Garden in New York in 2006 © Scott Gries/GettyYet, by the mid-2000s the Korean Wave still had not reached beyond Asia. That would require the emergence of technology that would bypass traditional channels and in the words of one industry insider, inject Korean content “straight into the bloodstream”.

In January 2006, a 23-year-old Korean singer called Jung Ji-hoon — otherwise known as Rain — played two concerts at Madison Square Garden in New York. His 2005 album, It’s Raining, had sold more than 1m copies across Asia, and he was regarded by many in the Korean music industry as their great hope for breaking into the US market.

Despite attracting the curiosity of the American media, however, Rain’s US tour did not achieve its objectives. While attracting large numbers of Korean-American and Asian-American fans to his shows, the crossover success that would later be achieved by acts such as Psy, BTS, and Blackpink eluded him.

“The only way of finding mainstream success in the US at the time was through traditional media outlets such as TV, radio, and the printed press,” says Cho. “It was just before the dawn of social media platforms — he missed out by just a few months.”

Customers take pictures next to BTS-themed decorations outside a McDonald’s restaurant during the launch of the BTS Meal in June 2021 in San Fernando, Pampanga province, the Philippines © Ezra Acayan/Getty THE 'SECRET SAUCE' OF SUCCESS

Customers take pictures next to BTS-themed decorations outside a McDonald’s restaurant during the launch of the BTS Meal in June 2021 in San Fernando, Pampanga province, the Philippines © Ezra Acayan/Getty THE 'SECRET SAUCE' OF SUCCESS

Michael Hong, a former chief executive of ImaginAsian TV, the first 24-hour Asian-American television channel in the US, bears the scars of years of trying to convince American executives to take Asian content seriously.

“In the pre-digital era, the barrier to entry was very, very high — you would get put in this ethnic media ghetto,” says Hong, who now distributes digital content from around the world. “It’s not that the executives were bigoted, necessarily. But they go by the numbers, and we didn’t have the metrics to convince them.”

Even before the rise of social media, K-pop groups enjoyed dynamic relationships with their digitally savvy fans. Producers would constantly experiment with a dizzying array of musical and visual genres, inviting fans to upload their responses and imitations. That in turn would create a fierce sense of community between fans as they praised, encouraged and quarrelled with each other, turbocharging online engagement.

"Korean fan culture has always been about active participation, about making your own videos, about joining in and getting involved with fan groups,” says Hong. “In return, the groups are constantly acknowledging their fan bases. That creates a dynamic like a sports team, when the group’s success becomes their own.”

The timing could not have been better. “Korean fan culture fitted perfectly with YouTube culture; Korea’s cultural moment coincided with the rise of technology that could deliver it to the world,” says Kwon.

Focused principally on overseas consumers, Korean distributors placed great emphasis on the sophistication of the metadata attached to their content, making it easier to be found by non-Korean speakers on American and European platforms.

“As sexy and slick as K-pop videos are, it’s actually something as mundane as the metadata that really set them apart [from other foreign language competitors],” says Cho. “It’s the secret sauce: you can’t fall in love with something if you can’t find it.”

“That’s the main difference with Japan and China,” says a Korean industry executive. “For the Japanese, foreign markets were an afterthought. The Chinese cut their platforms off from the rest of the world. But for the Koreans, it has always been about exports.”

According to Kwon, “the Japanese had the right idea when Sony bought into Hollywood. Their misfortune is that they peaked too early.

“Japan’s cultural moment occurred in the age of the video cassette” he says “the Koreans had YouTube. There’s no contest.”

Psy on stage at the MuchMusic Video Awards in Toronto in 2013 © Canadian Press/ShutterstockThe online momentum being gathered by Korean pop acts would break into the open in 2012, when Psy’s Gangnam Style — the most-viewed music video ever on YouTube but originally aimed at a domestic audience — emerged as a global phenomenon. But it would be almost a decade until a Korean drama, Squid Game, which has been viewed over 100m times, achieved a comparable impact.

Psy on stage at the MuchMusic Video Awards in Toronto in 2013 © Canadian Press/ShutterstockThe online momentum being gathered by Korean pop acts would break into the open in 2012, when Psy’s Gangnam Style — the most-viewed music video ever on YouTube but originally aimed at a domestic audience — emerged as a global phenomenon. But it would be almost a decade until a Korean drama, Squid Game, which has been viewed over 100m times, achieved a comparable impact.

Passed up by numerous Korean companies, the dystopian drama was produced by Netflix as part of its focus on “glocal” content: locally-produced shows that capture market share in target countries and regions while being fed into an ever-expanding bank of content for consumption by over 200m subscribers worldwide.

Netflix has spent Won770bn ($650m) on Korean content over the past five years, and is, it says, planning to invest another Won550bn in 2021 alone.

That investment may have brought Korean content to the world’s attention. But it also highlights the scale of the challenge facing Korean entertainment companies seeking to increase their market share. South Korea may have gained the plaudits for the success of Squid Game, say observers, but Netflix made the money.

“There is a limit to relying on Netflix too much,” says Park Hyuck-tae, industrial policy team leader at KOCCA, which coordinates development and promotion of the Korean content industry. “Netflix is giving a margin of just 10-15 per cent to Korean production studios, and taking all the intellectual property rights for the content. That’s why people say it is Netflix that is making most of the money, despite the huge success of Squid Game.”

Merchandise for boy band BTS on display at Hamleys toy store in London Merchandise for boy band BTS on display at Hamleys toy store in London © Justin Tallis/AFP/Getty

Merchandise for boy band BTS on display at Hamleys toy store in London Merchandise for boy band BTS on display at Hamleys toy store in London © Justin Tallis/AFP/Getty  BTS perform at the American Music Awards in Los Angeles in 2020 © Big Hit Entertainment/GettyEXPLORING THE 'METAVERSE'

BTS perform at the American Music Awards in Los Angeles in 2020 © Big Hit Entertainment/GettyEXPLORING THE 'METAVERSE'

Seo Jang-ho, senior vice-president at CJ ENM, South Korea’s largest film and television producer with a market capitalisation of over $3.4bn, says that while it is more realistic to take advantage of global platforms “for the time being”, his company will “seek ways to strengthen Korean platforms in the long-term”, including through investment in his company’s streaming operation.

Underlining the Korean music industry’s global ambitions, Hybe Corporation — formally known as Big Hit Entertainment, the company behind BTS — in April completed a $1bn merger with Ithaca Holdings, an American management agency whose clients include the likes of Justin Bieber and Ariana Grande. Smaller agencies are also expanding internationally, exporting their business models by offering consulting services and pop star training programmes.

At the same time, the Korean gaming sector, which dwarfs those of K-pop, film and television is buying into Korean and western content producers and companies specialising in creating virtual worlds known as the “metaverse”.

In a sign of the creeping convergence of sectors once regarded as distinct, Korean gaming company Com2uS has invested both in US studio Skybound Entertainment and in WYSIWYG, a Korean metaverse company specialising in visual effects technologies. Another gaming company, Netmarble, in August created a partnership with Korean production group Studio Dragon and launched a subsidiary called Metaverse Entertainment to explore the production of interactive content involving virtual pop stars.

This has translated into a proliferation of metaverse platforms where users can use cryptocurrency to purchase digital assets such as virtual clothes, videos, or parcels of land. Korean entertainment companies JYP Entertainment, YG Entertainment and Hybe all have stakes in Zepeto, a K-pop and fashion-focused avatar platform backed by Naver, a Korean tech group. Four out of every five users of Zepeto, which has its own digital currency, are teenagers; Blackpink, the all-girl group signed to YG, held a virtual signing event on the platform last year.

“Korean entertainment companies want to be the platform providers of the future, offering multiple services and sucking in data,” says Kwon of the Korea Economic Institute of America. “It’s ultimately through data, not media content, that they move up the value chain.”

In May, the South Korean government launched a “Metaverse Alliance” of over 200 companies and institutions. It has earmarked almost $8bn from its 2022 budget for the country’s next digital transformation. The hope, it appears, is that the country can repeat the trick of the late 1990s and again steal a march by adopting next-generation technology earlier and more enthusiastically than everybody else. If so, say observers, it is a manoeuvre aimed at contesting not the present dominance of Netflix, but the potential future dominance of another US technology group: the company formerly known as Facebook.

For many Koreans, however, the future should not be allowed to distract from what has been achieved so far: global recognition and critical acclaim that means more than sales of cars or chips ever could.

“The part of you that maybe you were suppressing — the Korean part of you — all of a sudden that part of you is shining, and it just makes you whole,” says Hong, who grew up in Queens in New York.

“You’ve never seen so many prominent Asians looked upon as equal, you never saw those images,” he adds. “We’re contributing something to the culture that’s not watered down, that’s not derivative — it’s the ultimate validation.”

https://www.ft.com

By Christian Davies (Additional reporting by Song Jung-a and Kang Buseong in Seoul)

Featured Commentator : Bernie Cho [DFSB Kollective]

Friday, February 3, 2023 at 8:24PM |

Friday, February 3, 2023 at 8:24PM |  DFSB Kollective

DFSB Kollective  // EXCERPT 1 //

// EXCERPT 1 //