NBC LX : Late to the K-Pop Wave? Here's a Guide to the Phenomenon Sweeping America

Wednesday, June 23, 2021 at 9:33PM |

Wednesday, June 23, 2021 at 9:33PM |  DFSB Kollective

DFSB Kollective

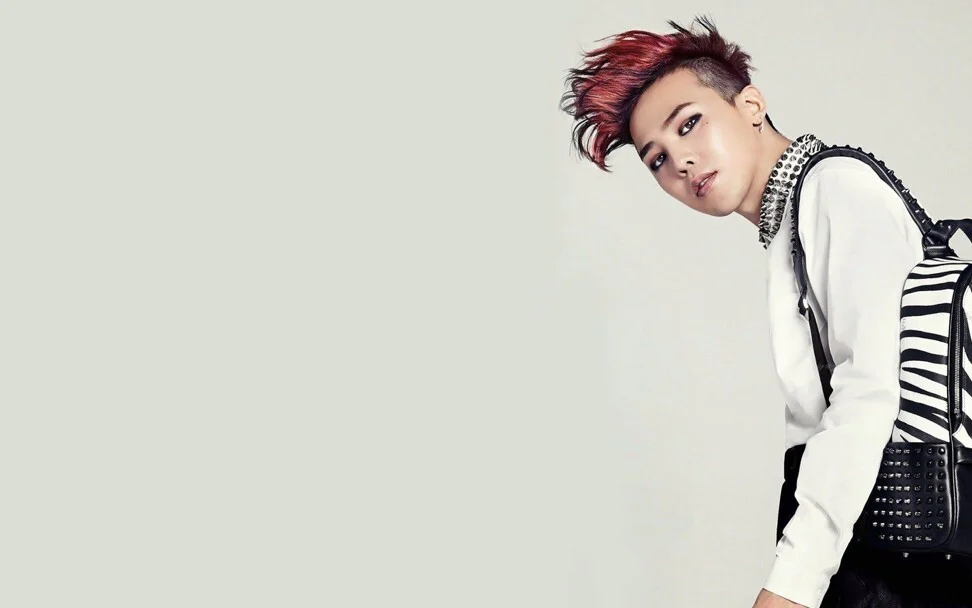

BTS, the biggest band in the world, recently released 'Butter', a strong contender for song of the summer coming off their record-breaking single 'Dynamite.'

In case you haven't been paying attention... K-pop is a really big thing in America. Like...REALLY big. But while it may be new to some in the West, K-pop (Korean pop music) has existed for almost thirty years.

From Netflix dramas to ten-step Korean skincare routines, Americans are enamored with Hallyu — the Korean cultural wave. But while television shows and skincare are popular, nothing compares to K-pop with its catchy hooks, difficult choreography and stunning visuals. How big is Hallyu? As music executive Bernie Cho says in the Youtube documentary K-Pop Evolution, “Korean pop culture is the third-largest [consumer goods] export industry for Korea,” bringing in 9.5 billion in 2018.

BTS, one of the biggest bands in the world, recently released "Butter," a strong contender for song of the summer coming off their record-breaking single "Dynamite." If you’re new to the genre, don’t worry. Here’s a helpful primer:

HISTORY OF K-POP

Prior to the democratization of South Korea in the late 1980s, the government controlled what music citizens had access to. The new government structure ushered in more exposure to western music and culture, influencing a new generation.

A trio of Seoul natives, Seo Taiji and Boys, made their television debut on a Korean talent show in 1992. The song, "Nan Arayo (I Know)" blended American new jack swing, hip-hop and rock. The judges hated it, giving Seo Taiji and Boys the lowest scores of the night. However, the public loved this American-influenced sound and quickly propelled the single to the top of the charts where it stayed at number one for eighteen weeks and went on to sell 1.7 million copies.

Seo Taiji and Boys made history not only with their unique sound but also with their lyrical content. They sang about mental health, societal norms and teen angst in a way that resonated with the younger population of Korea. Although the group disbanded in 1996, they paved the way for big studios to develop the genre into what it is today.

WHO ARE THE MAJOR PLAYERS?

In the nineties, three mega entertainment companies formed to make what industry insiders call “The Big Three” K-pop record labels. SM Entertainment (1995), JYP Entertainment (1997) and YG Entertainment (1998) honed the method of creating idol groups that is still the standard in 2021.

The first idol group formed by SM Entertainment in 1996 was H.O.T., a five-member group composed of singers, dancers and rappers. Their boyish charm, fun choreography and loud fashion resonated with the audience and cemented them as one of the first successful idol groups. S.E.S, A trio of teenage girls with bubbly songs and choreography soon followed.

Today HYBE Entertainment, the home of BTS, is perhaps the biggest player in the game with their recent label acquisitions including Scooter Brauns’ Ithaca Holdings. Bang Si-Hyuk, a former composer for YG Entertainment, founded Big Hit Entertainment in 2005. Until recently, BTS was the only group on the label. Big Hit Entertainment has now rebranded to HYBE Entertainment, home to K-pop elites, BTS, TxT, Enhypen, Seventeen and American superstars Ariana Grande, Justin Beiber and Demi Lovato.

K-POP BECOMES AN INTERNATIONAL PHENOMENON

While H.O.T. found success in China, BoA crossed over in Japan, and Super Junior became huge in France, it took a bit for K-pop groups to reach the United States. That changed in 2009 when JYP Entertainment marketed Wonder Girls to the American public. The five-member girl group had a distinctly retro look that was more 60s Motown than 2000s K-pop. Wonder Girls went on tour, opening for The Jonas Brothers and gaining a smattering of American fans.

While Wonder Girls exposed a subset of Americans to K-pop, the next decade blew the door open. In 2012 singer Psy became a worldwide phenomenon with "Gangnam Style," a song about the trendy residents of the Gangnam District of Seoul. The humor, costumes and simple dance routine resonated with people all over the world with the music video becoming the first to hit a billion views on YouTube.

Psy was a fun fad in America but the next K-pop act had staying power. Two primetime award show appearances in 2017 exposed millions of Americans to seven young men from Korea about to change the game, starting with their win for Top Social Artist Award at the Billboard Awards. If viewers were curious about BTS at the Billboard Awards, their performance at the 2017 American Music Awards earned them an onslaught of new fans.

BTS has continued their momentum setting numerous billboard records, selling out stadiums and earning a Grammy nomination. They aren’t the only group finding success in the States. Blackpink made history at Coachella, Monsta X became the first K-pop group to release a full English album that charted on the Billboard 200, and acts like Seventeen and NCT have successfully sold out arenas across the country.

MAKING THE FAN CONNECTION

What sets K-pop apart from other genres is the connection artists have with fans. K-pop groups have built loyal fanbases through constant interaction, relatable lyrics and shows of affection. Fandoms have specific names, lightsticks, and individual organizations within the fan base promoting charitable activities and social justice causes. K-pop fans may often be mislabeled as teeny-boppers or fanatics through the media. But these organized fan bases are the reason K-pop is thriving.

“The fandom plays a critical role in keeping the idols relevant. Especially in an industry where new groups appear every day, and where many groups are often 'ranked' against each other on performance shows and contests," says K-pop DJ and podcast host Peter Lo. "Fans are the sustaining power who go through great lengths to increase view counts, download figures, social media comments, and album sales to keep idols at the top of the charts.” He added that “labels often orchestrate parasocial relationships that reward fandom behavior which drive chart rankings and album/ticket sales.”

The fans form bonds with their favorite idols through not only music but live stream conversations, fan meetings, reality shows, documentaries and consistent social media content. BTS often takes filmed trips where viewers may see Jungkook, the youngest member, doing laundry while bandmates Suga and Jin make dinner for the group.

THE FUTURE OF K-POP

"Butter" is sure to bring a lot more radio play for BTS this summer, but is K-pop on track to be the biggest genre in the world? Music journalist Tassia Assis says “in terms of popularity I believe it might reach a state like anime and manga have in the West” with passionate fan bases and endless staying power. Some are gambling on larger mainstream success by bringing K-pop to primetime television. Both Hybe and SM Entertainment have recently made deals with Universal Records and MGM Worldwide to produce reality show competitions that will put together American versions of K-pop groups.

As far as the evolving genre, Lo predicts a content transition. “We'll see more short-form content optimized for short hooks that look good within the video resolution of an iPhone screen. This has already had a profound impact on music production trends — favoring songs which have a sudden genre/mood shift which performs well on short-form content platforms like TikTok,” he said.

With big money and international recognition also comes big business. “I suspect we'll also likely see further consolidation within the K-pop industry.” Lo added, “Hybe is making moves to create a sustaining model for a future without BTS by acquiring many major labels.”

When questioned about K-pop in the American market during a global press conference for their latest release, RM, the leader of BTS, said “K-pop has become less a genre and more like an entire industry.” It's an industry that shows no signs of slowing down.

YOUR BEGINNER'S GUIDE TO K-POP PLAYLIST

https://www.lx.com/culture/entertainment

By Emily Mallon [NBC LX Contributor]